Artist Steven Siegel inches toward becoming one with nature Yonhap News Agency Seoul, South Korea 2016 http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/interview/2016/11/23/1/0800000000AEN20161123007700315F.html

Biological, Geological, Temporal

http://hotelhotelblog.com/2013/04/11/biological-geological-temporal/

Critic's Pick Artforum February 2011

Steven Siegel’s latest mixed-media installation, Biography,2008–10, is an epic seventy-five-foot-long mishmash of color and material that spans two massive walls. Shaggy carpet, fuzzy fabrics, and hundreds of tightly wound bundles of newspapers are harnessed on wooden planks and interwoven with a mess of gadgets, gizmos, and colorful craft supplies. From afar, Biography looks like a vast topographical map: Cables and hard drives and twinkly lights mime cities; thick black piping and power cords seem like strips of highways; the spines of newspapers resemble the color and texture of beach and mountains; and fluffy carpets in rich browns and oranges recall aerial views of farms.

As with most of Siegel’s work, an environmental critique is implicit—in Biography the litter of consumerism composes the look of our world. But the piece is complicated by its composition. Materials like plastic and polyester are mixed with beads and yarn, bound into brilliantly colored bunches and laced into a chaotic harmony. Much like Jackson Pollack, who organized a shambolic mess of paint into symphonies of color and texture, Siegel commands the detritus of our culture into a frantic rhythm, nailing contemporary anxieties about the environment to the wall. Siegel may image our world out of rubbish, but the result is ravishing, glittering, and glistening in all its synthetic, inorganic wonder.

Still, the objects in Biography are the pieces of our environmental crisis––pernicious, toxic, sometimes unrecyclable items that pollute our air and increasingly dominate our earth. As a result, this prodigious mass of art bursts with ambiguity: Siegel simultaneously trumpets our colorful wealth of objects and reminds us that consumption is, for better or worse, the cover of the twenty-first-century biography.

The Sculptor from Planet X John Perreault Artopia February 15, 2011 (click on link)

http://www.artsjournal.com/artopia/2011/02/steven_siegel_the_sculptor_fro.html

Click image for cover article by Patricia Phillips

Click image for cover article by Patricia Phillips

Into the Holocene: The Art of Steven Siegel

Dutchess Magazine February, 2000

By Karin Bolender

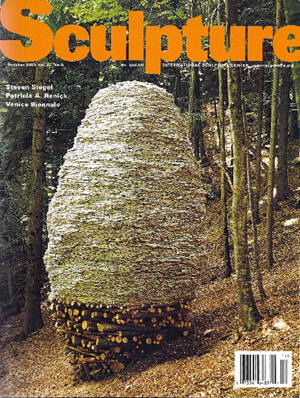

New Geology #2"New Geology #2," an organic timepiece made of newspaper, stone, and flora in the woods by the artists home in Milan, was a breakthrough in his artistic exploration of the fate and endurance of terrestrial matter. Photo courtesy of the artist

"Deep time," so named by the writer John McPhee, is one of those daunting truths that can prove rather unyielding to the human psyche. The term relates to geology, and its source originates around 1780 at a place called Siccar Point in Scotland, where the seminal geologist James Hutton first discovered the earths processes of erosive breakdown and uprising renewal had been going on a heck of a lot longer than previously suspected. Hutton's "angular unconformity" exposed in a Scottish seaside headland, confirmed a theory of geological time that slowly let the hot air out of the prevailing anthropocentric cosmology, disproving the theological calculation that Earth was created especially for humanity and delivered at 9 a.m. on Oct. 26, 4004 B.C. What Hutton witnessed in the rocks inclined the age of the earth more toward untold hundreds of millions.

In his book Basin and Range, McPhee explains the significance of Hutton's discovery, with the following analogy: "Consider the earths history as the old measure of the English yard, the distance from the king's nose to the tip of his outstretched hand. One stroke of a nail file erases human history."

Not surprisingly, deep time is almost, but not quite, inconceivable to the human mind. If nothing else, it can be simply terrifying. It is so far to the edge of our understanding of ourselves and our mortality that it almost seems irrelevant. To some, anyway.

But then there are those minds who find provocative fascination in the old inhuman mysteries hidden in the subterrain; who are inspired and awed rather than threatened by the concept of the Paleozoic Era of 340 million years ago, or Precambrian Time, which precedes our own era, the Holocene, by some 2,000 million years. McPhee is one of these. He was thrilled by the power of language to interact with this vastness, the unknown and unfamiliar depths of time, bringing its complexities and mysteries into our understanding, as much as it can. As he writes in Basin and Range, "Geologists communicated in English; and they could name things in a manner that sent shivers through the bones ... There were dike swarms and slickenslides, explosion pits, volcanic bombs. Pulsating glaciers. Hogbacks. Radiolarian ooze. There was almost enough resonance in some terms to stir the adolescent groin."

Certainly there were enough resonances in the concept of deep time to spark a lasting inquest in the imagination of a young visual artist and wanderer of Western landscapes. Which is exactly what and where Steven Siegel was when he first read McPhee and began a career long artistic interrogation of the essential cycles of deposit and decay that underlie the making of the land. As a visual artist rather than a scientist or writer, Siegel's creative engagement with the structures and processes of deep time took a different form than McPhee's; for Siegel, the desire to investigate latent geological realities was a matter of delving simultaneously into the substrata of the land and of his own imagination, through the process of constructing his own visible manifestations.

In 1983, Siegel's fascination with geology compelled him to go out and spy certain significant formations for himself With sponsorship from the New York Foundation for the Arts, he traveled to Siccar Point to have a look at Hutton's fateful "unconformity" the place where deep time first became a scientific reality. He says this face to face encounter was "one of the most profound moments" of his ongoing dialogue with mineralogical matters. "All you're really seeing when you look at a landscape is a moment in time. Once that idea took a foothold in my mind, then I really started to get interested, " says Siegel.

In the spring of 1998, Siegel was in residence at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wis., assembling the materials that made up his contribution to "Labyrinth," a collaborative effort of several artists. Photo: courtesy John Michael Kohler Arts Center/Doug Green.

He brought this inspired understanding of geological events and cycles back home and into his Lower East Side loft. There in his studio he set to interpreting the processes of stratification and compression in the compositions and forms of his prints and sculptures. He pushed slowly further with this way of working, gaining insight and skills in tiny increments, digging toward the truest substantialization of his vision: "I had been thinking about this stuff for years, and I'd been doing all these beautiful, formal works on paper and in sculpture, using what Id learned in art school And then I was given an opportunity to do an outdoor piece. I resisted it at first. It forced me in a new direction."

The work was to be for the Snug Harbor Sculpture Festival in Staten Island. As you may already know, Staten Island is also the location of the world's largest landfill. For one who had been contemplating the hidden materials and substructures of the land for so long, the encounter with Staten Island turned out to be a kind of revelation. "If they're putting all of this junk down into the earth," went Siegel's thinking, "what's under there is a new geology that we've created."

Working in three dimensions and within what he terms "a very simple set of parameters," Siegel began to materialize this concept of the New Geology. A series of time bound structures, built of post consumer wastes such as plastics and rubber and newspaper, formed from the same old earthly operations intrinsic to the mystery of matter. The first piece, "New Geology #1," was his contribution to the Snug Harbor Festival, but he did not feel it was an aesthetic success. With the realization of "New Geology #2," however, Siegel could see he was "onto something."

As the spirit of his work suggests, it is the tiny elements and minor events over the course of time that make up the drama of the whole. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Hudson gallery features earth-centered sculpturesThe idea of using post consumer materials was one thing, but the real breakthrough was in his artistic process. "I began trying to somehow act as nature rather than interpret it. Sedimentation in part seemed to be the most accessible thing to emulate." In a bog near his home in Milan, Siegel began laboriously stacking layer upon layer of newspaper. Ton upon ton. "I immersed myself in a very labor intensive process where 1 used a very slow, methodical way of working. It was more about letting the process itself take control."

Integrated into the woods and exposed to all its forces and weathers, "New Geology #2" was a kind of experiment with material time. So many of the erosions and compressions and accumulations that make up the earth as we know it are literally a matter of certain physical forces transforming substances over duration, according to the way certain material behave and are changed by these forces. Uncertain what would happen, Siegel watched the laden block of paper freeze solid right along with its environment in the winter, then pale and decay and cohere as the rain and forest light and microflora and fauna acted on it. "Over time, the paper took on a shale like quality. It broke down much slower than I thought it would," says Siegel. And in the springtime, it bloomed. "That was a real breakthrough."

While "New Geology #2" has more or less disappeared into the landscape, Siegel has spent the last 10 years building on the idea. With every new manifestation, he refines the building technique, from a use of increasingly sophisticated engineering to a growing base of "skills in orchestrating and composing [the sculptures]." He has stacked newspaper and other post consumer materials, along with native wood and soil and flora and stone, all over the world.

Each new piece is conceived and built onsite, using indigenous materials (such as tons and tons of local newspapers) and available labor; thus it is made integral, in its way, to the surrounding landscape. Often it is left alone to break down as it will, its transformation making a Slow, quiet, but still startling testament to the constant pressures of time operating on every kind of matter indiscriminately.

Like any other, the "idea" of Siegel's "piles of newspaper," as he calls them, can be simplified, but that does not mean it is simple. While the environmentally relevant concept of using post consumer waste materials in his artwork has gained him success in the art world, he says it is not really the aspect of the work that interests him most. Nor is he out to make a political statement about the environment or anything else, preferring to keep separate "politics and imaginative acts."

This is not to say Siegel is oblivious to the state of the planet, or even that his artwork does not in some way rise out of that concern. Undeniably, his works focus needed attention on the wastefulness of consumer culture and the depletion of Earth's natural resources. With the same shock and shame we should all feel, he reports how "Americans comprise 5% of the world's population, and consume 35% of the world's resources." But what leads him to make art is not the impulse to speak out about these issues. To put it as simply as possible, Siegel says his sculptures exist because he wakes up in the morning, like all visual artists, "with a compelling need to see something."

To word it another way, his artworks are not statements at all; they are questions. Speaking in broad terms, you might say an artist mines the imagination for the rare rough diamonds, the hardest truths within the mysteries of being in space and time. As the author Clarice Lispector says in her deathbed novel, Hour of the Star, "So long as there are questions to which I have no answers, I shall go on writing."

Melding his own artistic process to the basic physical processes that make the land, Siegel builds forms that echo the mysteries he perceives resounding in the old, old rocks and beyond them: what's behind these natural processes of accumulation and decay, tension and compression? What do they mean in and of themselves? And what do they mean for people, how we live, what we use and what we lay to waste? How can we understand our role on earth when it seems each one of us has no more significance than a peanut in a black hole? How could it possibly matter what we do as individuals, in light of all this?

For Siegel, the greatest motivation to continue to make sculptures is that the questions are always there to be asked. Just looking at different landscapes, particularly the younger, volatile ones of the American West, he finds an "endless reservoir of source material." Of course there is something to be said for the maturation of an artist's work, too, the way individual pieces become ever more articulate in the way they pose particular questions. Take for instance a recent work of Siegel's called "Very Slow," which he completed in early 1999 for the permanent collection at The Fields Sculpture Park in Omi, New York; the piece consists of two hulking towers of layered newspaper, rising up and bulging ponderously within a spindly grove of maple trees. It is a striking embodiment of his persistent inquiry into the way "small, light things over a tremendous period of time become dense, heavy things."

For an artist, or scientist, or any kind of human being really, sometimes the unfailing need to ask the same questions over and over again can become a kind of answer in itself. Where Siegel's work exists, the most salient question perhaps is one of the relationship of a person, caught like a bug in a tiny mortal moment, to the old primal earth. But the nature of the question is what defines the artwork in the end. In Siegel's work, the subtle transmission of meaning through inquiry may be in the fact that the question is "how do the natural forces of time and decay and accumulation act on earthly matter?" And in this formulation, humanity is not separate from the category of earthly matter, but part of its awesome whole. The real inspiration comes when someone grasps that deep time is not a threat to one's personal significance, but a vast enfoldment in which one's little light husk becomes part of something venerable and profound.

Siegel explains it this way: "We are part of this amazing system, this universe that is so far beyond our comprehension. I never run out of inspiration; I feel like I'm plugged into something that's so big, I can just take as much as I want whenever I need it." The understanding that he articulates here, more so than any horrifying facts about the rate at which humanity is destroying the earth's balance, may just be the founding principle of an ecological consciousness.

With all this in mind, you can look at "New Geology #2," for instance, and imagine the seasons coming and going around and within it, the light and plantlife rising and failing against a background of deep time with the flickering briefness of fireworks flaring up and fading away against the fathomless blackness of the night sky. And you see that even if the works that come out of this digging for (or building toward) the rarest truths hidden in time and earth are never really conclusions as such, they are often scraps of beauty at least. Which is a kind of answer anyway.

Hudson gallery features earth-centered sculptures

Daily Freeman June 8, 2001

By MARY CASSAI

"Collage #5, mixed media, 1999, 19 x 23 x 9"

STAND IN FRONT of the church opposite the Davis & Hall Gallery at 362 Warren St., Hudson, and look across to the display window. You'll see a handsome Panamawoven basket filled with brilliantly colored fabrics. Not until you get up close do you realize that sculptor Steven Siegel's Witsion is created from discards like tightly compressed paper. But even with the illusion stripped away, Siegel's work is a thing of imagination and beauty.

BETTER KNOWN for his large, site specific public sculptures installed throughout the United States and Europe, the Milan resident's current exhibit is comprised of smaller studio works: abstract, crafted sculptures and wall pieces created from some of the same postconsum r materials that he works with on a larger scale such as paper and rubber tire shreds.

A brilliant article by Karin Bolender titled "Into the Holocene: The Art of Steven Siegel," (Dutchess Magazine, February 2000, pages 25 27) explains the source of Siegel's inspiration. As a young artist, he was moved

by author John McPhee's discussion of "deep time," in his book "Basin and Range." Siegel, too, became fascinated by the processes through which discarded matter is transformed over time, and so "began a career long artistic interrogation of the essential cycles of deposit and decay that underlie the making of the land ... He set to interpreting the processes of stratification and compression in the compositions and forms of his prints and sculptures."

Material for "Squeeze 2" (1998. Newspaper and sod, 8 x 10 x 12 ft.), Siegel's site specific sculpture at Appalachian State University, North Carolina, for example, was drawn "Collage #5", mixed media, 1999, 19"x23"x9", by Steven Siegel entirely from a college newspaper collection campaign. A brief in "Sculpture" magazine (March, 1999) points out that Siegel's goal in the larger pieces is to create a symbiotic relationship between the sculpture and the environment. He prefers to work with non stable materials. "Squeeze 2," designed to last about two years, would then, according to the artist, "get more interesting over time as the paper slowly changes appearance and starts to host various molds, fungi, insects, and flora."

This is what drives Siegel: the visual impact of his biodegradable sculptures on their surroundings, and their gradual transformation as the elements impact on them over time. He is not interested in making a political statement, about saving the planet, for instance, or crying out against greed and waste. But his works do raise questions, about time and our place in it, about what can be done with human detritug.

THE WONDERFUL THING about this new exhibit of Siegel's smaller works is the ease and intimacy of interaction. All his materials are earth related, all informed by the same dynamic principles, the layering, the compression, the transformation, that drive his larger pieces. Reduced to wall hangings and table pieces, they are more accessible, even, in some sense, more powerful.

The show's signature piece, "Collage #5" (Mixed media. 1999. 19x23x9") combines several hemispheric, compressed structures with stone, tree bark and branches. The yellows, whites, taupes and burgundy browns of this work are accent. ed by a jet black overlay of shredded carbon material. It's a corsage fit for Mother Earth herself.

"Big Rubber" (Rubber, cloth. 2000) is a one eyed mass of skull shaped rubber, the eye socket packed with fabric: white for the eyeball, dark blue for the pupil. "Carbon #1' (Mixed media. 2000) starts as a deflated old tire; but when struck by Vulcan's fire, it becomes a living thing.

"Mixed Media No. 6" suggests a telephone directory gone wild: hundreds of long strips of white paper, tightly compressed and mixed with petrified, sanded forms, are capped by carboniferous material.

Among the free standing pieces, "Tabletop #10" is fashioned from tightly compressed layers of paper set into a driftwood support, while "Cans and Sand" is formed of objects flattened, dredged in sand, and glued together in a mass resembling a hornet's nest.

Layer on layer of tar paper narrows gradually toward a base, creating the dense whirlwind of "Felt." The graceful, convoluted shape of "Doubletree" is particularly attractive, with black painted branches growing out of two nests formed from layers of stone and styrofoam.

AFTER THIS EXHIBIT, you will never again be able to pass a rock formation without intense scrutiny.

Not to be missed at Davis & Hall is the awesome Sculpture Garden exhibit by James Welty: five giant (about 12 feet tall) copper sculptures on steel discs, a fitting counterpart to Steven Siegel's earth related motif. This is fantastic statuary in every sense of the word, an Alice inWonderland world created for adults. A gargantuan effort of repousse, hammering forms from the wrong side and then fusing the sheet of metal, was required to form the bulbous, hive like eruptions on the copper "flesh" of Welty's creatures, and then burnishing the work with fire. Among them are "My King," equipped with peculiar appendages like banana legs feet of crushed gourd, and a winged phallus, and wearing an African royal hat of tightly wound wire; and "Monster," suggesting a female mannikin, stomach burst open in a cosmic wound, copper lid blown off like a batch but still attached. Most curious of all is the frog shaped mouth at the base, smoking a gourd shaped cigar.

Last stop is the Davis & Hall Carriage House, four levels of sculptures and ceramics by John Cross, John Ruppert, Grace Knowlton, Paul Chaleff, Chris Griffin, Robert Paasch, and, of special note, Gillian Jagger, whose massive (3 stories high), "Huddle 11" (Wood. 2001) celebrates the limitless forms locked inside a tree.

Mary Cassel is a free lance writer on the arts living In the Hudson Valley.